Vol.14

A Modern Suki-ya Style Space to Immerse in Nature

Masamichi Katayama (Wonderwall®︎)

NOT A HOTEL KITAKARUIZAWA MASU, to be built in the lush Kitakaruizawa mountain area north of Tokyo, takes inspiration from both Japanese and modernist architectural styles. We talked to its creator, the renowned interior designer Masamichi Katayama of Wonderwall®, about how MASU hybridizes West and East.

The sukiya-style and modernist architecture

The initial pitch to Mr. Katayama for NOT A HOTEL KITAKARUIZAWA MASU was not just to build something for a specific site, but to dream up a universal, easily replicable concept for a vacation home. “Traditional Japanese architecture feels quite modernist in that it's often based on a standardized system.While learning from that approach, I also wanted to propose something with a special depth, and that led me to the home of Kenzō Tange, one of the pioneering architects of Japanese modernism.”

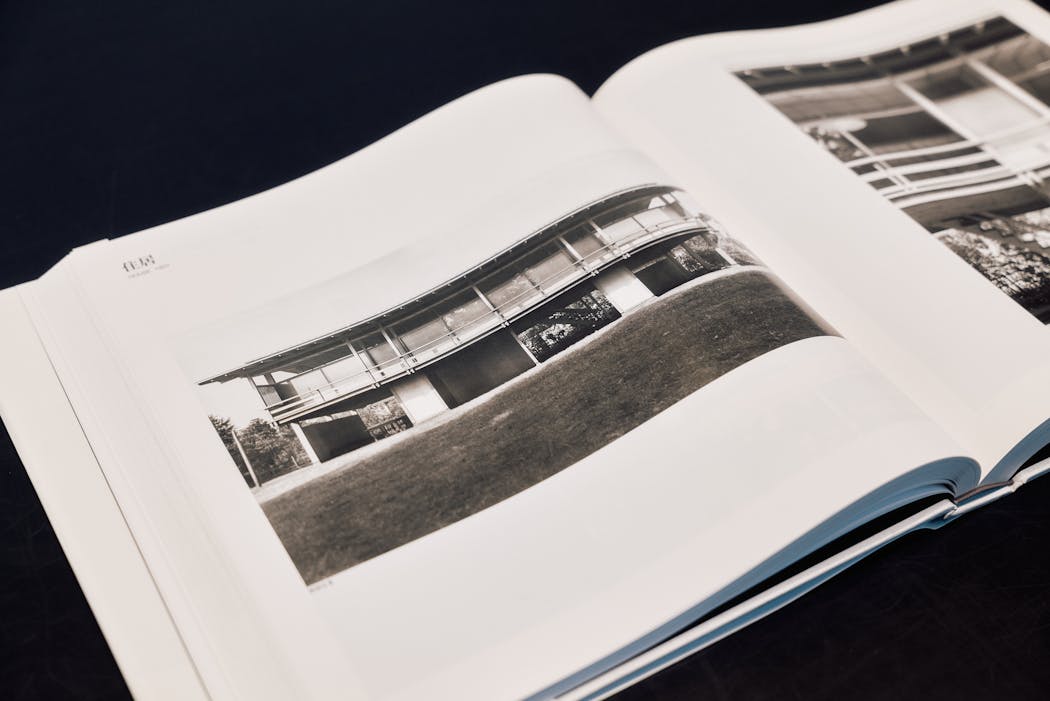

The Tange residence, completed in 1953, is an experimental piece of wooden architecture in which the first floor uses just pilotis, and the second floor is a continuous living space with tatami-floored rooms. The house no longer exists, and Mr. Katayama’s fascination with it began after he saw a scale model at an exhibition. “Although it is very Japanese, the home has elements of internationalist style as well. Traditional Japanese architectural styles include shinden-zukuri and shoin-zukuri. The Katsura Imperial Villa, which Tange drew inspiration from, has a raised structure with shoin arranged in a zigzag pattern. At the same time, it also realizes Le Corbusier's concept of pilotis — an open ground floor supported only by pillars, creating an open, breezy space. This architecture, which combines Japanese and Western ideas, is highly open while still ensuring privacy, which I found incredibly appealing.”

Mr. Katayama explains that Katsura Imperial Villa combined characteristics of various Japanese architectural styles and also qualifies as sukiya-zukuri. “To put it simply, sukiya refers to the architecture of a tea room created specifically for enjoying tea, built separately from the main residence. While it could be considered a style, it also has its own identity as a specific kind of architecture. At the same time, there are no rules to the style, many tea masters and architects have embraced the challenge of pushing the boundaries of sukiya architecture through their unique expressions.”

“Living the Life of a Modern Suki - As you like it.”

The word sukiya comes from the term “someone with a preference,” referring to a sophisticated person who has a penchant for the elegant. Mr. Katayama says that the concept of NOT A HOTEL overlaps with this concept, as the owners of NOT A HOTEL are people who enjoy staying in a special space separate from their main homes. “I was thinking about the way people used to enjoy the time doing tea ceremonies in the past, and now you can enjoy a wider variety of hobbies and time in such spaces. That is what a modern sukiya should be.While consciously drawing upon the influences of the Tange residence, sukiya architecture, and modernism into realizing NOT A HOTEL KITAKARUIZAWA MASU.. The overall concept boils down to this: “Live the way you want.” This came out of Katayama's personal wishes for his own vacation home, and from thinking about building a space that would give energy to those who visit.

www.mir.no.jpg?w=1050&auto=compress)

“Tange's conception of achieving modernism while paying homage to tradition was so strong it can’t be altered. We expressed our originality instead by creating a space with an element of entertainment that can be enjoyed in a slightly more casual way than a residential home. At NOT A HOTEL KITAKARUIZAWA MASU, half of the floor space on the first floor is occupied by an open dining room, the other half by pilotis. And an outdoor living room with a fireplace is placed in front of the space, creating a close relationship with the forest. The second floor is a living space that maintains privacy, with a deck covering the entire surface. High sash windows in all of the rooms allow everything to be opened up while being integrated into the environment. I wanted to create a space that would give the people who stay there an opportunity to really feel nature.”

Making architecture like you make furniture

“I'm not an architect, but an interior designer. That's why, when I think about space, I approach it with a focus on even the smallest details, down to the millimeter,” says Mr. Katayama. He cares a lot about design, but his training also focuses him on the durability of the building structures. This is one of the key points in creating beauty: pushing the limits of what’s possible from both design and strength perspectives.

www.mir.no.jpg?w=1050&auto=compress)

The thin pillars are made to look like wood but are created by welding iron plates together. The proportions of the second floor deck and roof have been carefully thought out, making you feel as if you’re gently floating in the forest of Kitakaruizawa. “Of course, beauty means nothing without functionality. After carefully examining the details of the roof, pillars, deck, etc., we decided on the form, and also examined the expression of the materials by looking at reflections, gloss, etc. It was like making architecture the way we make furniture. I believe that we will create a space where on first glance it doesn’t look that unique, but after a while, you realize there's something different about it.”

Stairs are one example of where Mr. Katayama becomes obsessed with details. Grand staircases often appear in the masterpieces of modernist architecture, and Mr. Katayama says, “Moving between floors creates sequences in the space, and I think it's because the stairs are a device that creates an extremely important scene. We carefully reconsidered the plan many times while considering factors such as the riser (the height of one step of the stairs), the tread surface (the top surface of the tread on which you place your feet), and the relationship between the first and second floors. We thought of the stairs as an object that would define the architecture.”

A fusion of East and West that pays homage to the mid-century period

Until a few years ago, Mr. Katayama wanted to distance himself from Japanese culture. But then he realized that his favorite architects had interpreted and expressed Japanese culture in their own way. Over the past few years, he has come to appreciate Japanese design by coming face to face with the best and most modernist elements of his native culture. Sukiya architecture became a way to freely express what he liked. “Always keep your eyes open and your ears open. When you do this, interesting information will come to you. I want to take in that information and cherish the most mind-altering experiences in my daily life,” says Katayama. The elements that stirred his own emotions have been incorporated into various parts of NOT A HOTEL KITAKARUIZAWA MASU.”

The furniture inside NOT A HOTEL KITAKARUIZAWA MASU also reveals the influence of Japanese culture on architecture and design around the world, and Katayama’s desire to stay close to that. “For this project, I took another look at history and chose my favorite furniture mainly from the mid-century period. This allowed me to express a clear fusion of East and West that has been the theme of my designs in recent years.”

All of home’s fixtures are original, and the design aims to create a flexible modular system similar to mid-century furniture. The delicate and beautiful finish of each piece is also surprising. “The space may look like it takes you back to a previous era, but for me, I think it's at the cutting edge of our contemporary era. A good way to understand yourself is to think about the places in which you want to stay. When I think that I myself may be able to stay here, I wanted to make it a space that I can enjoy. However, the more I thought about it, the more I removed my own ego from the project. Recently I have been making an effort not to design in this straight-forward sense, and instead reexamine the building’s essential meaning and role. This allowed me to approach the project with a fresh perspective."

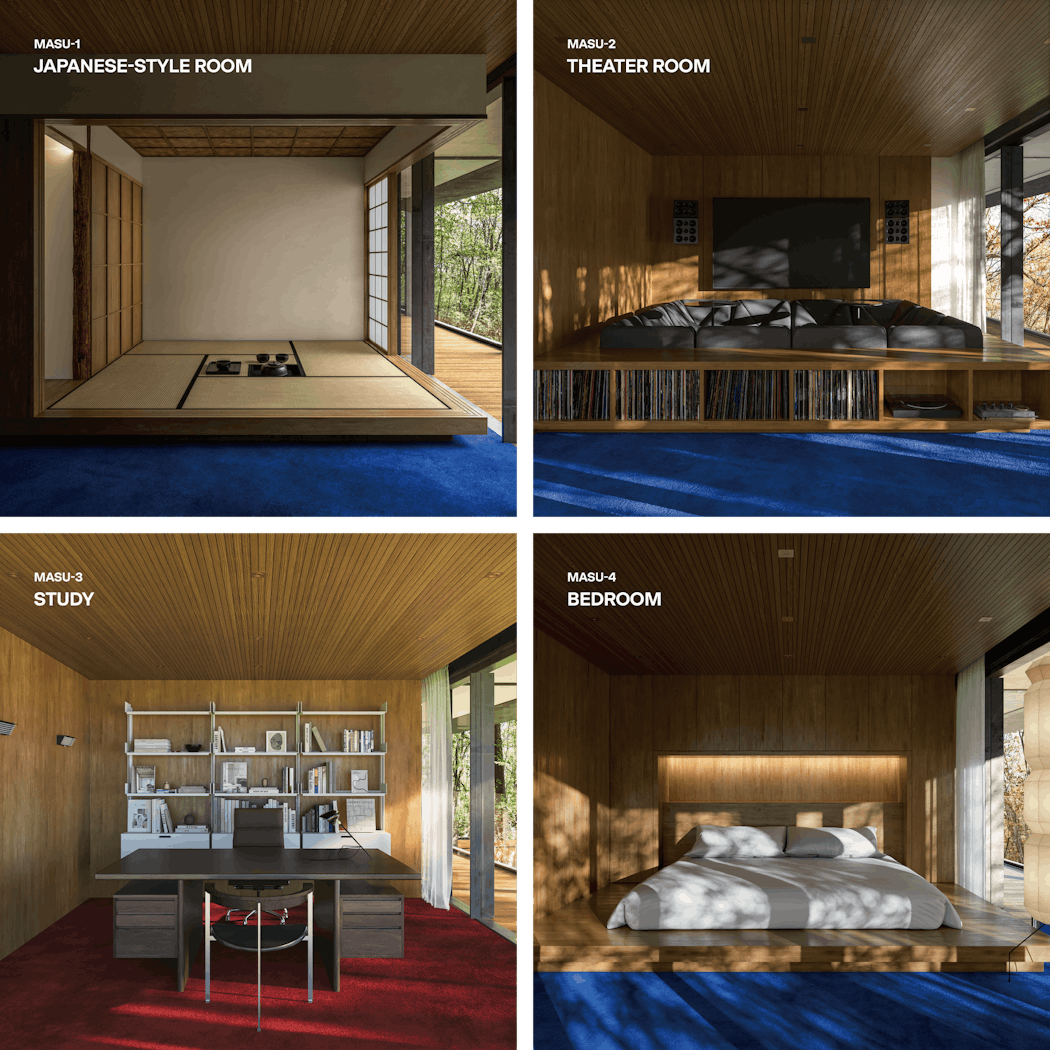

Each building has a different special masu creating a variety of ways to enjoy it.

The name MASU came from the floor plan, which resembles a combination of grids. (In Japanese, a “masu” is a square measuring cup used to weigh rice.) “When Mr. Hamauzu of NOT A HOTEL first saw the floor plan that we submitted, he said, ‘It looks like a masu.’ I thought it was interesting how this wordplay accurately expressed our concept, and I was excited that it could be seen that way.”

The idea is to play with the rules of the grid. “It was my first time to think about space with a grid system, but I was able to approach it in a systematic and bold way at the same time,” Katayama says. The second floor of NOT A HOTEL KARUIZAWA MASU, which is scheduled to have four buildings, will consist of eight grids, one of which will be a special grid with a different function and design for each of the four buildings. Each room will have its own unique personality.

“At NOT A HOTEL's request, we used two of the grids for the bathroom and sauna, which made the space very large. This may be considered irrational, but this is the kind of amazing thing that NOT A HOTEL is known for. Working with NOT A HOTEL pushes the designer more than with other clients. And this helped me feel like I’m providing a pure reflection of what is inside my head and heart at the moment."

Overall NOT A HOTEL KITAKARUIZAWA MASU is a vessel for appreciating nature with no limits on how it can be enjoyed. “I believe it will be a property that inspires people on every visit. Working with NOT A HOTEL gave this project a deep sense of reality in every stage. Perhaps this is why it speaks to us so vividly even before completion of the construction. I believe that this will be fully clear in the design.”

.png?w=120&fm=webp&auto=compress)

Masamichi Katayama

The renowned interior designer Masamichi Katayama is the founder of Wonderwall®, internationally recognized for its innovative approach to conceptual design and its ability to balance modern elements with respect for traditional style. The firm handles a diverse range of projects worldwide, from boutiques and branded spaces to the overall planning of large commercial facilities. Notable works include NOWHERE (BUSY WORK SHOP® HARAJUKU, the Japan House London, an overseas project spearheaded by Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, global flagship stores for Uniqlo in New York, Paris, and Ginza, and Tokyo Toilet in Ebisu Park. In 2020, Katayama received the Lifetime Achievement Award at the FRAME AWARD 2020, hosted by the design magazine FRAME (Netherlands). Wonderwall®︎ Official HP:https://www.wonder-wall.com/

WORKS

Japan House London

The JAPAN HOUSE project, initiated by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, serves as an overseas hub to deepen global understanding and appreciation of Japan. Guided by the principle of accurately conveying Japanese aesthetics, this large-scale facility includes spaces for exhibitions, retail, and dining, showcasing Japan's appeal to the world. Inspired by the concept of a "tokonoma" (alcove), the space embodies a uniquely Japanese quality where its atmosphere transforms with the objects and events it hosts.

SUIMONTEI

For the Suimontei project, Wonderwall revitalized a 1923 sukiya-style Japanese house in the historic city of Nara. The firm transformed the heritage property into a one-group-per-day accommodation and a membership café-salon. The design harmonizes modern sensibilities with the site's rich history, exploring contrasts across time (past and present) and space (East and West) to achieve a new balance. Rooted in a deep respect for historical context, Suimontei aspires to cultivate and share new cultural experiences.

THE TOKYO TOILET @ EBISU PARK

The Tokyo Toilet @ Ebisu Park is part of THE TOKYO TOILET, a public restroom project in Shibuya Ward spearheaded by the Nippon Foundation. Built within Ebisu Park, the project reimagines the restroom as an integrated park feature, blending seamlessly with its surroundings like playground equipment, benches, or trees. Drawing inspiration from the origins of Japanese toilets — primitive, minimalist structures known as kawaya — the design features 15 concrete walls arranged playfully to create an ambiguous space that functions as both a restroom and a sculptural park element.

STAFF

Text: Yoshinao Yamada

Photo: Kanta Nakamura(NewColor inc.)